In these posts I have often written about written about the horrors of slavery in the Guianas. What is less well-known is the form of slavery that existed at the same time among white people up in Labrador. Some may be unhappy with the comparison, and, it’s true, the Labradorians didn’t arrive in chains, were notionally free to leave whenever they wanted. But in many other respects it was the sort of slavery that is all too common day among 21 million people.

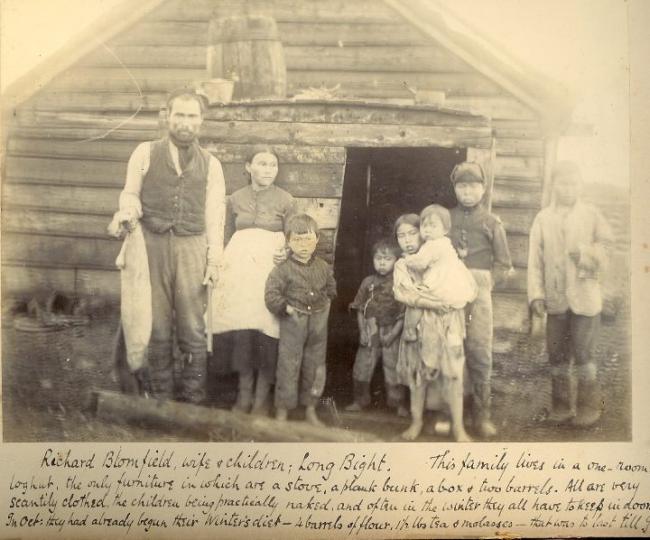

This is a picture of the white slaves, taken by my great grandfather, Dr Eliot Curwen (who was a doctor in Labrador in 1893). He often thought of his patients as slaves. It was slavery because of what was known as the Truck System. The idea was simple; the merchant sold the fishermen goods ‘on tick’ – whether nets, string, boots, lamp glasses, flannel, buttons or rice – all to be paid for in fish. ‘Cod is the coin of the country’ explained Curwen, ‘Money is scarcely known and no other medium of exchange is used … All live on goods advanced on credit, to be paid for by their catch of cod.’

Here lay the problem; the merchant fixed both the price of goods he sold, and the price of the fish he bought. In other words, he had the fishermen in his thrall. ‘The men’ says Curwen ‘became absolutely dependent on the charity of their merchants and in many cases from year to year did not know how much they owed … The spirit of pauperism was directly fostered.’ The system was ‘subtle because it impoverishes and enslaves the victims and makes them love their chains …’

So, the Labradorians were bonded into poverty. In fact, they were the poorest and most illiterate people in the Americas. They couldn’t argue or study – or even move away. ‘Many fishermen’ wrote one missionary, ‘never saw the colour of the dollar, and remained in debt to the merchant from the cradle to the grave.’ What’s so extraordinary about all this is not that the Truck existed but that it survived for almost two centuries. There was no law requiring wages to be paid in cash until the mid-1940s, long after his death.

‘The colony lives by the codfish caught,’ concluded Curwen ‘but in no wise recognises that the codfish-catchers are human’.