SEX AND SLAVERY. In the film, Mr Ebbs is portrayed as a rapacious predator, helping himself to a slave girl whenever he feels like. There is no question of consent, and she is entirely at his mercy (which is in short supply). Confused and piqued by her blank response, his interest soon takes a more sadistic turn.

Such tales are not quite as common as you’d expect in the history of Guiana. Certainly, John Stedman identifies a few psychopaths in his chronicle of the 1770s, and there may have been a great deal more rape that is not recorded. Carnality, however, was a complicated matter, and there was often a moment of hesitation before debauching a slave. This was partly because the African was an adept poisoner, and was known to be passionate in revenge. The other reason was economic: a pregnant slave was unprofitable one, and so it paid to avoid the casual conception. Slave-owners, as Dr Bancroft noted, went to great lengths to prevent such mishaps, deploying noxious lubricants of ocro and gulley root. Often these left the girls hopelessly infertile.

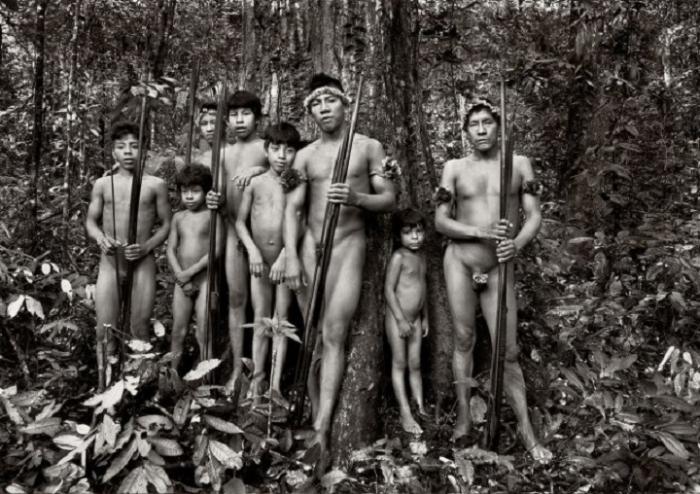

Occasionally, planters and slaves found themselves in consensual relationships (albeit that it was hardly a relationship on an equal footing). Just like in the film, the planters often installed slaves as their mistresses, and some Europeans – like Stedman – even entered into seemingly loving marriages (although the marriages weren’t recognised under Dutch law). Here is a picture of his wife, the beautiful Joanna.

Other unmarried planters entered into more commercial arrangements, often surprisingly enduring. ‘A European,’ writes Bolingbroke (c1780), ‘generally finds it necessary to provide himself with a housekeeper or mistress’. Females could be either rented at the fortnightly Stabroek Ball ($12 for two), or bought. However, ‘decent specimens’ were in such short supply that, often, they had to be imported from Barbados (a traffic run by ‘coloured women’, paid on commission). A ‘good, well-trained girl’, noted Bolingbroke, could be purchased for around £100-150, and ‘they are tasty and extravagant in their dress’. The best could read and write and ‘most are faithful and constant once an attachment has been formed’. They embraced all the duties of a wife, and, if children are produced, they were generally sent to England for education ‘at the age of 3 or 4 years’.

More often not, however, relations between slave-girls and their masters were tainted by that evil inequality. Here is how Stedman describes the end of a planter’s day: ‘His worship generally begins to yawn about ten or eleven o’clock, when he withdraws and is undressed by one of his sooty pages. He then retires to rest, where he passes the night in the arms of one or other of his sable sultanas (for he always keeps a seraglio) …’

(for more, read ‘Wild Coast: Travels on South America’s Untamed Edge’)