In a new twist to the Venezuelan renewed vociferous and heated claim to Guyana’s western Essequibo territory, eight opposition members of the Venezuelan National Assembly have presented a special bill for the creation of a new Essequibo “state.”

The legislators, Andres Velasquez, Freddy Marcano, Américo de Grazzia, Luis Barragan, Jose Manuel Gonzalez, Juan Pablo Garcia, Omar Gonzalez and Flores Leomagno, on July 15 presented their bill which proposes the creation of a state to be known as “Esequivo” (with a “v” in the spelling) to stretch from Sifontes, a municipality of Bolivar State, and including Guyana’s Essequibo territory claimed by Venezuela. They said that their proposed state would return the region to its “original name derived from its discoverer, Juan de Esquivel” and will constitute “an innovative, appropriate, timely and relevant popular representation in the framework of Venezuelan policy for the recovery of territory.” They viewed this action as legitimate, fair, and peaceful.

The eight proponents explained that the idea of the new state was conceived and developed by Sergio Urdaneta, a lawyer specializing in constitutional and administrative law, and that their proposal “is inspired by the best patriotic , sober and responsible feeling.”

In its preamble, the bill, published in the Venezuelan online periodical,Noticiero Digital.com, alleges that the Paris arbitral award of October 3, 1899 “amended” the Constitution of the country and reduced Venezuelan territory by 159,500 square kilometers. It further claims that the award was never ratified by the Venezuelan State and therefore it remained without any validity.

Strangely, the eight parliamentarians have not included in their proposal for their proposed state the chunk of 10,350 square kilometers of territory west of the Rupununi District, granted to the then British Guiana by the 1899 award, but which was later ceded by the British government to Brazil after another arbitration in 1902. This area bounded by the Takutu and the Cotinga River (in Brazil) was originally claimed by Venezuela before the arbitral tribunal.

The bill also asserts that the award “was achieved by coercion,” thus closing the proponents’ minds on the fact that it was actually the British government that was forced to agree to arbitration in 1897 by the American government which at that time heavily backed Venezuela in its territorial claim.

With regard to the structure of their proposed “Esequivo State,” the provisional capital will be the city of Tumeremo in the Sifontes municipality. The governor “is required to be Venezuelan by birth, over twenty-five years and a layman.” For this purpose, a Venezuela is considered to be to anyone born in the territory “which includes the Esequivo territory.”

The bill goes on to explain that legislative power will be vested in the new state by a legislative council comprised of between seven to fifteen members, elected for a term of four years by the voting majority.

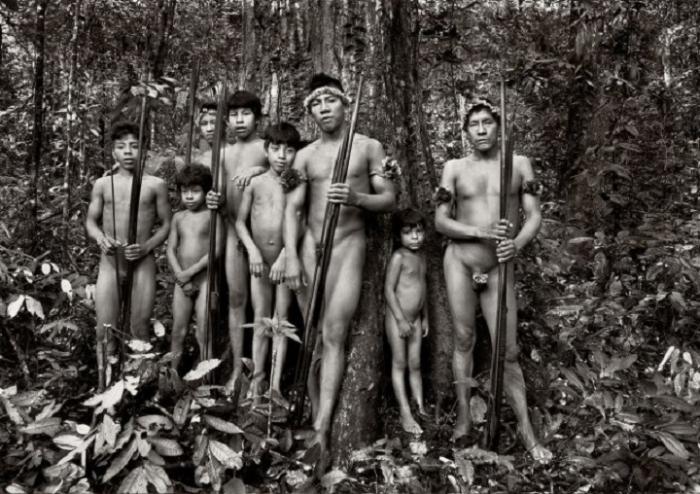

And the territory of the proposed state will be organized into municipalities, parishes, communes, departments, cantons, and captains, and “recognizes any geographical, historical, cultural features and realities of the inhabitants of the territory.”

Apparently, the proposers of the new state feel that it is good enough for a governor and the legislative council to “be elected by the population that makes up the municipality of Sifontes until the register of the remaining territory of the state is completed.”

The eight National Assembly members indicate optimistically in their bill that when passed, the legislation “shall be published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Venezuela in Spanish, English, Macuchi and Wapishana.”

How much support the bill will garner is not yet known, but in recent days, both government and opposition members of the National Assembly have shown strong unity in backing President Nicolas Maduro in his vehement demand for Essequibo. Only recently, on July 14, the National Assembly voted unanimously to support him, with almost no criticisms from the opposition. And on the following day, they applauded his establishment of a presidential commission for border issues. In this test of patriotism for his opponents, they have passed with flying colors. They in turn will surely demand their pound of flesh, and the proponents of the “Esequivo” bill must be thinking that they will be able to garner much needed support from parliamentarians on the government side. On the other hand, it may still fizzle out since the Venezuelan government has more challenging economic issues to handle at this time.

However, the entire concept of a new Venezuelan state encompassing Guyana’s Essequibo territory assumes, erroneously, that Guyanese citizens residing there will gleefully accept Venezuelan citizenship. Nevertheless, it presents a dangerous ploy to the Guyanese nation, for this bill comes right out of the playbook of European revanchists of the nineteen and twentieth centuries and even more recently, who laid similar types of groundwork before the acted to annex neighboring weaker territories.