In a secret Memorandum by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs titled “Grant of Air Facilities to the United States” dated July 18, 1940 it was stated that in a May 24, 1940 telegram, the British Ambassador in Washington, DC USA “outlined proposals for the grant of naval and air facilities to the United States in neighbouring British colonies and Newfoundland.”

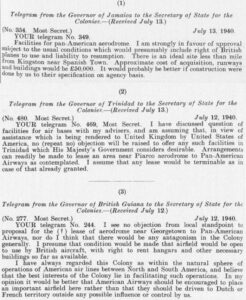

The memorandum included telegrams from the Governors of Jamaica, Trinidad and British Guiana stating that they had no objections in allowing the U.S access to airport facilities in their respective countries. (See scanned Image)

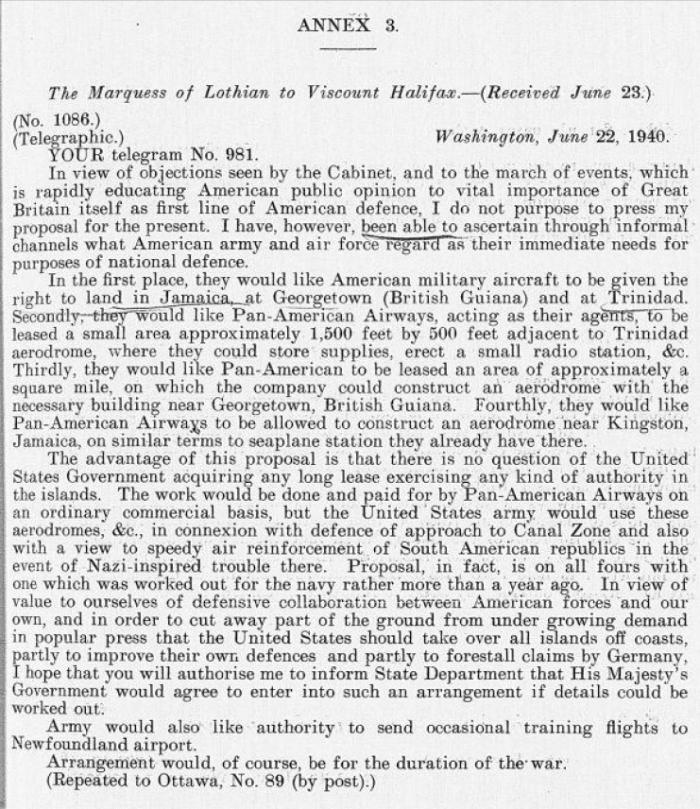

Excerpt

These proposals were strongly endorsed by the Chiefs of Staff Committee in their aide-memoire W.P. (40) 174, but were rejected by the War Cabinet at their 146th (40) meeting on the 29th May, 1940. The decision of the War Cabinet was conveyed to Lord Lothian in a telegram of the 2nd June (Annex 2). On the 22nd June Lord Lothian replied (Annex 3) intimating that, whilst in view of the War Cabinet’s objections he did not propose to press his proposals, he would be grateful to receive authority to inform the State Department that His Majesty’s Government would agree to enter into the following arrangements, which he had ascertained through informal channels would meet what the American Army and Air Force regarded as their immediate needs for purposes of national defence.

(a) Facilities for United States military aircraft to land in Jamaica, Georgetown (British Guiana) and Trinidad.

(b) A lease to Pan-American Airways, acting as agents of the United States Government, of a small area near the Trinidad aerodrome where certain facilities would be required.

(c) A lease of approximately a square mile for an aerodrome in British Guiana.

(d) Permission for Pan-American Airways to construct an aerodrome near Kingston, Jamaica.

(e) Authority for the United States Army to send occasional training flights to a Newfoundland airport.

2. Following upon interdepartmental discussions, it was suggested to the Chiefs of Staff Committee that Lord Lothian’s above-mentioned proposals should be considered. I understand, however, that the Committee’s full endorsement of the Ambassador^ earlier and wider proposals applied a fortiori to the more restricted facilities now suggested, and that there was, therefore, no occasion for a further report on their part. Lord Lothian’s latest proposals have been referred to the Governors of Jamaica, Trinidad and British Guiana, who are in favour of their adoption so far as local considerations are concerned (see their telegrams attached as Annex 4). The Government of Newfoundland (Annex 5) see no objection to proposal (e) above, and the Canadian Government (Annex 6) have replied that they consider it highly desirable that the facilities in question should be afforded. In subsequent telegrams Lord Lothian has emphasised the need for an urgent favourable response to his recommendations (i) because of the rising popular demand in the United States that all the Caribbean islands should be acquired in the interests of American defence, and (ii) because the question of acquiring all Caribbean islands may possibly be raised by the Latin American Republics at their forthcoming conference at Havana, which is to open on the 20th July. Lord- Lothian has also drawn attention to the fact that Congress has just voted large sums to enable Pan-American Airways to construct aerodromes in South and Central America, and he expresses his conviction that by hook or by crook this expenditure will be made effective for aerial defence for the whole of the Central American region.

3. Whilst there is force in Lord Lothian’s argument that by making the offer recommended in his telegram of the 22nd June it will prove possible to stave off wider demands, the main argument in favour of action in the sense proposed is that it corresponds to a realistic view of Anglo-American relations both in the present and in the future. For not only do we require all the help we can get in the present, but the future of our widely scattered Empire is likely to depend on the evolution of an effective and enduring collaboration between ourselves and the United States. This may be an obvious necessity for us, but for America it is a new and startling doctrine.

4. Our aim should surely be to; assist America in the task of assuming a new and heavy responsibility for which so little in her tradition and history has prepared her. A successful relationship between the two English-speaking groups implies not only an assumption of responsibilities on America’s part but, equally, a generous recognition by us of the fact that a responsibility involves a right to the means for discharging it. Until late in the last war it was Great Britain, almost alone, who for nearly a century had guarded the English-speaking peoples by sea, and it is still the British Empire, rather than America, who possesses the naval and air facilities (actual and potential) which protect the American continents. But in future we may well neither be capable of performing these functions unaided, nor can we reasonably hope for cordial co-operation from America unless we share with her the strategic facilities which these duties will require. At this very moment it is only fair to recognise that if Britain were to be defeated America would have the task of defending her eastern shores without any prepared air bases under her own control in the Atlantic Ocean. It seems inconceivable that America should tolerate such a situation, or that anything except bitterness could result from a failure on our part to recognise it.

5. The practical alternatives open to us would seem to be either to make America a free offer of the immediate facilities she needs or to drive a bargain and attempt to obtain some specific quid pro quo in exchange. The second alternative is open to the objection that we are already heavily in debt to America as a result of the last war, and that we shall shortly be still further in her debt as a condition of winning the present war. We have no hope of ever repaying the enormous sums which will be involved, nor do well informed Americans ever expect this of us.

6.The Americans are hard bargainers, but they are generous and large hearted friends, and they do not stint their kindly impulses. Thus, thousands of our poorest children are being offered homes on the other side for the duration of the war, but we have not been asked for anything in return. Nor did it occur to any American that the modification of their neutrality laws, shortly after the beginning of the war, might be made the basis of a “deal.” It is with America’s consent, and very much against her immediate economic advantage, that we maintain our. contraband control. She could break our blockade of Europe to-morrow if she wished, and thereby greatly ease her political and economic relations with the republics in the Southern Continent. For none of these things does America exact a price from us.

7. If our aim is to foster a habit of cordial co-operation between the English-speaking countries, this can hardly be achieved on a basis of “tit for tat”; it can only develop through the habitual exercise of friendly assistance freely given, together with a general recognition of the other country’s needs and feelings. It must in any case be remembered that it is not within the power of the United States Government to grant any substantial concessions to us, e.g., destroyers, without the consent of Congress, which depends in turn upon the evolution of public opinion.

8. On grounds of immediate advantage and also of our future relations with the United States I would therefore suggest that Lord Lothian should be authorised to offer to the State Department, without asking for any quid pro quo, the facilities immediately required by the United States Army and Air Force detailed earlier in this paper, subject to such temporary safeguards as may be required by His Majesty’s forces, for the duration of the war. Unless, however, these safeguards are kept to an absolute minimum, not much of value will be left to offer to the Americans, and in practice the added security resulting from closer and more cordial relations with the United States should in the long run abundantly outweigh any security we could obtain by pursuing a narrowly self-centred policy.

July 18, 1940.