Paula Liverpool had the guts and motivation to work as a bartender in a notoriously dangerous Miami strip club, but she could not muster the nerves to watch her daughter, Sachia Vickery, play two sets of tennis Monday.

Too emotionally wracked to sit in the stands at Court 7, Liverpool instead watched the score change on the huge video screen in the south plaza. But she did not have to wait long to reunite with her daughter. Vickery required only 42 minutes to thrash Iva Mekovec, 6-0, 6-1, and advance to the second round of the United States Open girls’ draw.

A steadily rising star on the American tennis scene, Vickery, 16, has made it this far in her young career with a combination of talent, court savvy, desire and great athletic genes.

But if not for the uncommon dedication of her mother, who worked two jobs so that her daughter could continue to play, Vickery might never have gone any further in her tennis life than hitting a paddle ball off the wall of her modest home in Miramar, Fla.

“What she has done for me is inspiring,” Vickery said Monday. “It’s helped me to grow stronger as a person. When you’re not used to getting everything easily, you fight harder for it. Every time I go on the court, my mentality is, fight, fight, fight. It’s helped me, so I’ll never complain.”

Whatever is the typical path of the typical American tennis phenom, Vickery has not followed it. She rode buses to tournaments with her grandmother, left the United States to play in France, and spent recent Christmases with LeBron James, whose mother, Gloria, is like an aunt to her. (Vickery’s former stepfather, Derrick Mitchell, lived with Gloria in Akron, Ohio, and a young Sachia would visit. They remain close.)

But Vickery was always more impressed with her idols, Serena and Venus Williams, than she was with LeBron. She has had tennis on her mind ever since her grandmother bought her a paddle and ball at a dollar store.

She relentlessly hit that rubber ball against the house, declaring she would become the next Serena. Eventually her mother realized she would either have to get her on real tennis courts or watch her destroy the house.

By the time Vickery was 8, she showed promise, and was put in touch with Otis Johnson, a former Jamaican professional who moved into the family home and remains with her to this day.

“I was supposed to stay for a week,” Johnson said, “and it’s been eight years now.”

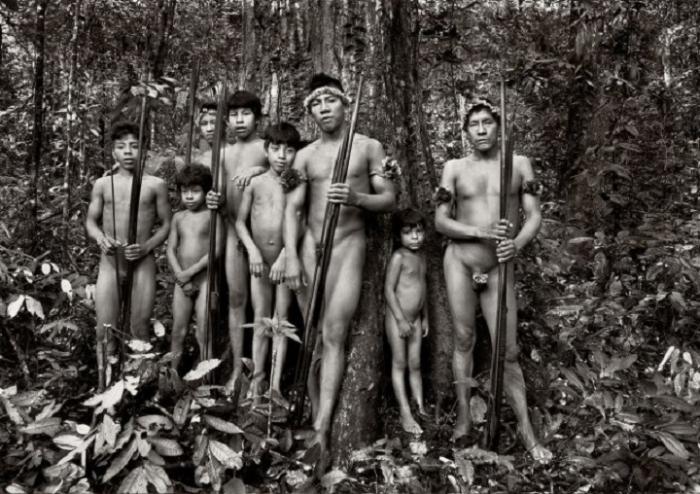

Johnson worked mostly free, but as Vickery progressed, her tennis expenses outpaced Liverpool’s earning power as an administrator for Kaplan online university. Liverpool, who immigrated from Guyana after earning a degree in education, knew she needed another job.

“Sometimes, for the love of your child, you do things you never, ever thought you would do,” Liverpool said.

She was offered a job tending bar at Club Rolexx, a so-called gentleman’s club, from the part owner Carl Cruise. She would be fully clothed, but still would have to endure leering men, loud music and occasional gunplay.

“The first time I walked in there, I walked right out,” Liverpool recalled. “I said: ‘Carl, are you crazy? I have two degrees. I’m not going to work in there.’ It was something I was totally opposed to. But I needed the money so I just kept my eyes closed and did my job. Sometimes, things that are the opposite of what you believe in morally, you have to do for your children.”

One night in 2008, a patron standing no more than 10 feet from Liverpool was shot in the leg. Another time a manager of the club and her friend were shot in his car as he left. But each time, Liverpool went back to work the next day.

At first, Vickery did not know what her mother’s job entailed. When she found out, she pleaded with her to stop, concerned about the crude atmosphere and potential for violence.

“I was really scared because it’s in a really bad area in downtown Miami, and she said a few times they had shootouts there,” Vickery said. “So, every time she left I was so scared, at night. I was just praying. I told her to stop, but she said: ‘I have no choice. Right now, that’s what I have to do until otherwise.’ ”

Even with the extra income, it was a struggle. While many of Vickery’s contemporaries were driven to country club lessons or flown to tournaments, Vickery rode 12 hours on a bus from Miami to Atlanta. It was annoying and perhaps embarrassing, but it made her hungrier.

“She would ask why she had to take the Greyhound bus,” Liverpool said. “I told her, ‘All the other kids are going to get there in their planes and their Lamborghinis, and you are going to kill them all.’ Sachia won both tournaments.”

As she gained more notice, Vickery spent a year at the I.M.G. Bollettieri Tennis Academy in Bradenton, Fla., before again breaking the mold. She spent the last two years at the Mouratoglou Tennis Academy in France, where few American players go to train. Her mother finally quit the strip club, and she and Johnson joined Vickery in France.

Although her recent ascent was slowed by knee tendinitis, Vickery, who is ranked 496th in the world, has been healthy this year and made the semifinals of a $25,000 tournament in Bogotá, Colombia, in July, and the final of a $10,000 event in Guadeloupe in January.

“I have always believed in Sachia,” Kathy Rinaldi, the U.S.T.A. national coach, said in an e-mail. “She has incredible foot speed and balance. Has improved her forehand and serve. I think she can go far if she puts the work in.”

Putting in the work should not be too hard. It runs in the family.

Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/06/sports/tennis/young-tennis-stars-talent-is-matched-by-mothers-dedication.html?_r=2&