Caribbean Studies Symposium:

Caribbean redefined – “ bona fide sociology of Caribbean literature” urged!

By Lin-Jay Harry-Voglezon

If the day long engaging symposium on “the current state of Caribbean research” held on April 17 at Brooklyn College, is evidence of new thinking then Caribbean academics are leading a new path of Caribbean identity and sense of self. The multidisciplinary discourse presented by the 13 Caribbean Professors and DJ Rupture (Jace Clayton) on Caribbean immigrant communities was partly in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Caribbean Independence. Sponsored by the Social Studies Department of Brooklyn College, subjects ranged from urbanization, community gardens, gentrification, “race, gender and identity in carnival”, Caribbean musical genre and instruments, “authors meeting critics”, to “texting the diaspora”.

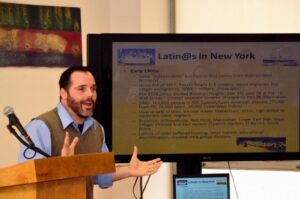

Each presentation in some way illustrated dynamics and hybridizations of the Caribbean identity in the metropolis and conditions under which it survives, conforms and transforms. The principal context of reference was New York as it is a center of transnational communities and place of Caribbean immigration preceding Dutch and British arrivals. The first New Yorker was Juan Rodrigues from the Caribbean said Professor Alan Aja. He was of Spanish and Yoruba ancestry from the Dominican Republic; a linguist who spoke and wrote several languages, married an Indian native and settled in 1513.

So the Latino and Caribbean presence in the US has a long history said the Professor. He noted, there were always waves of migration “back and forth” between the US and the Caribbean, occasioned by the fluctuating fortunes of European and US colonialization, production of gold, sugar, fruits, etc. Caribbean immigrants in the US have common roots, he added. This was not clarified but the professor, seemingly constrained by time to get through his quantitative trajectory of immigration patterns, was clear that US and European fortunes, acquired through exploitation of Caribbean lands is missing from US education.

This, he suggests, prejudices the presence of Caribbean immigrants, and their descendants who are faced with identity questions. “Community gardens” said Professor Miranda Martinez, was a way by which Puerto Rican immigrants dealt with that reality. The gardens became controlled public spaces for communication of culture, creativity, experimentation, sense of self and place, and re-enacting themselves as a “relational people”. But that is displaced by community upgrading and gentrification.

So “what is it like to be a person with a Caribbean ancestry and identity living in Brooklyn?” Professor Jennifer Adams, in focusing on “place based education” as a strategy pursued for teaching science in context of a community’s identity and environment, answered this question with her developing theory of “multi-place” identity. It posits that a people not indigenous to an environment may construct a sense of place and self “connected to multiple places at once through history, memories, identity, and lived experiences”. Afro-Caribbean descendants for instance, are grouped as, and living the experiences of, Blacks in America. They may never visit the Caribbean but ethnically identify with the Caribbean through parental cultural transmissions. They may relate to the norms of America that they were born into but at the same time choose traditions, practices, “a style of clothing, musical tastes and use of language”, for example, that’s identifiably Caribbean. They experience “conflict of space”, for when in a Caribbean setting of festivals, sports, etc. they may feel free to enact a Caribbean identity, as Blacks in an American setting they may be subjected to surveillance and interrogation.

The lived experiences and history of Caribbean transnational communities begs the question, “What and where is the Caribbean?” Professor Adams also suggests that the Caribbean be defined and understood in terms of place and space.

Professor Anton Allahar of Western University, Canada, and former President of the Caribbean Studies Association supported that suggestion in the boldest of the presentations. He challenged Caribbean academics and Americans to recognize that the Caribbean is “much wider, much more diverse, much broader, much more rich” than we are generally aware of. It is “complex but not complicated” he said. He considers the State Department’s description of the Caribbean as a “Caribbean Basin” derisive, and travel agent’s convenient contraction and expansion of definition unacceptable.

Geographically, the Caribbean is all the English, Spanish, French, Dutch and other language speaking territories within precincts of the Caribbean Sea. Spacially it is political, psychological and social, said the professor; it is the primary source from which the Caribbean diaspora derives, transforms, maintains and contests its identity.

Said Professor Allahar, the Caribbean is seen as a “place where black people are shaking off their colonial shackles”, have lots of rhythm, fun, and people with white teeth, and where white people are not safe alone or in small groups. He contended that content analysis of web pages of Caribbean organizations, shows that the Caribbean adds to this disservice by presenting itself as a place of beaches, “happy go lucky people”, wining, calypso and reggae. “You don’t get the sense that we have produced brilliant men” he noted, challenging Caribbean academics to produce “a bona fide sociology of Caribbean literature” rooted in our history to ground Caribbean people.

The greatest challenge is continued coherence within and without the diaspora, he observed; there are not enough courses and lectures on, nor people who study Caribbean Literature and pop culture. He argued that Caribbean Studies need to explore beyond slavery and colonialization, and suggests that indentureship, Caribbean women, economics, politics, Blacks, East Indian women, race, sex, age, nation, sexual orientation, region, and clan are worth investigation. He added, researchers need to examine whether the history and politics of globalization is the cause or solution of Caribbean problems.

They need to investigate social change as mirrored in Caribbean “amazingly rich literature”. He proposed that courses be introduced contrasting the philosophy and ideology of writers like V.S. Naipaul versus Samuel Selvon, Mighty Sparrow alongside Bob Marley, and the calypsonian as an organic intellectual. He argued that a Sociology of Caribbean women is imperative; icons such Vera Sico, Louis Bennette, Aunty Luke, Audrey Jeffers, should be studied.

He emphasized that the Caribbean needs a class “appreciation of the emancipatory political potential of our great writers” such as CLR James, Walter Rodney, George Lamming, Martin Carter, George Padmore, and Archie Seignham who though not from the Caribbean became such a Caribbean institution that there “should have scholarships in his name less we forget what he created for us, and have to reinvent the wheel.”

Noting that 10-12 Dutch Caribbean islands are hidden from our history, they should be explored. Similarly, “the diaspora within” should be. That is, the English speaking West Indian communities within Cuba (Bara gua), Columbia (San Angre, Providencia), Nicaragua (Bluefield), and Venezuela, who are descendants of the Panama Canal’s original diggers. Note, Afro-Antillean or West Indian communities within the Latin Caribbean also emerged from labor recruitments, especially while Britain held protectorates in Latin America.

The periodically filled Jefferson Williams’ Room, of academics and students from different locales in the US, were advised to examine the situational context and fluidity of asserted and ascribed identity in the Caribbean. The professor observed that regardless of whatever identity one asserts it is the identity ascribed to you that becomes most impacting. He illustrated that Haitians were massacred by Dominicanos because they were black. But the Dominicanos found out that they themselves were defined by Puerto Ricans as Blacks. Then the Puerto Ricans in the US were classified as Blacks. This “curious shift of race, colour and ethnicity in the region” should be researched.

Furthermore, the tensions between the diaspora and mother countries must not be ignored he said; there are conflicts of ideas, attitudes to premarital sex, remittance dependence and investment issues, which are impacting. A missing observation is that commemoration of the 5oth anniversary of the Caribbean independence could only refer to the English speaking Caribbean. Countries such as Cuba got theirs since May 20th, 1902 and Haiti’s since January 1st, 1804.